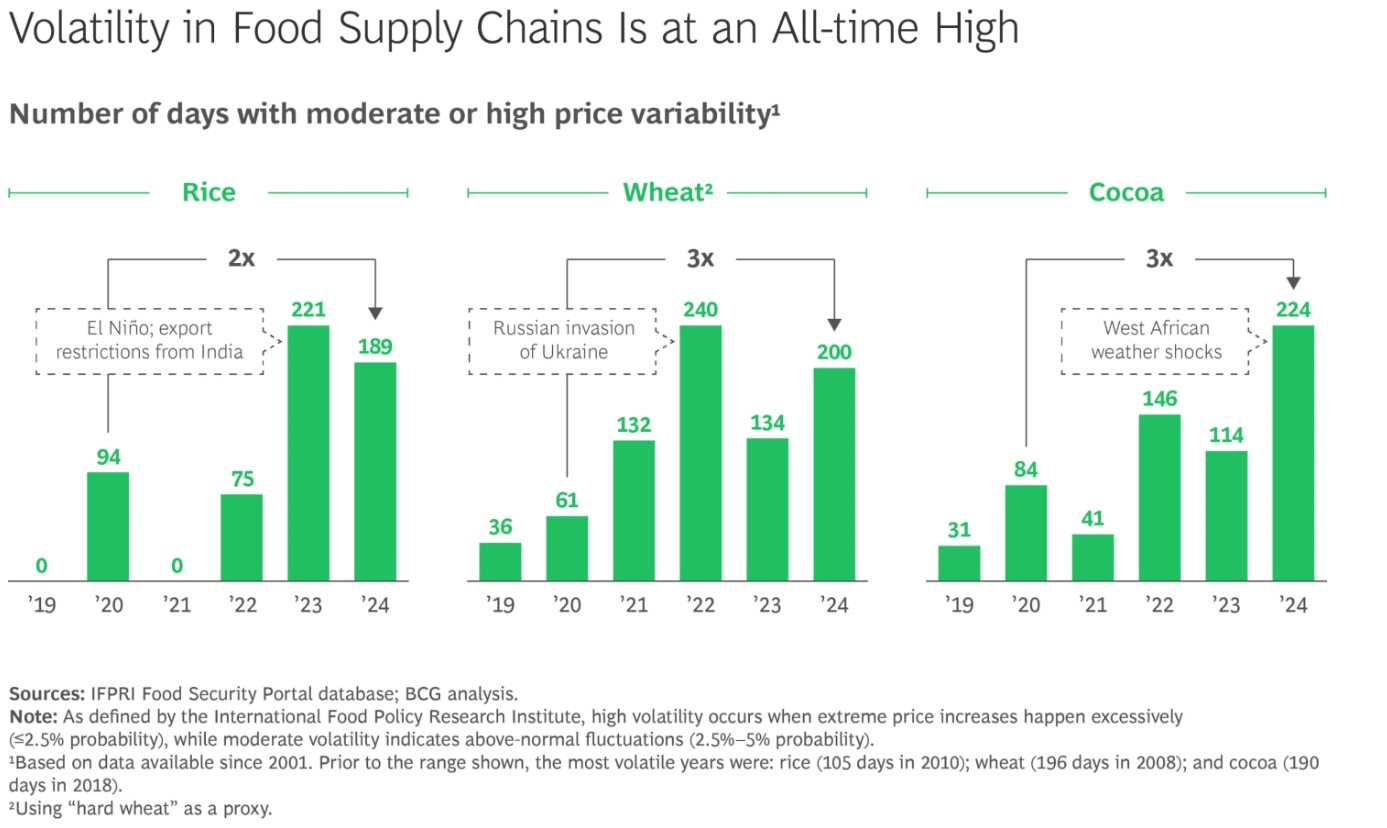

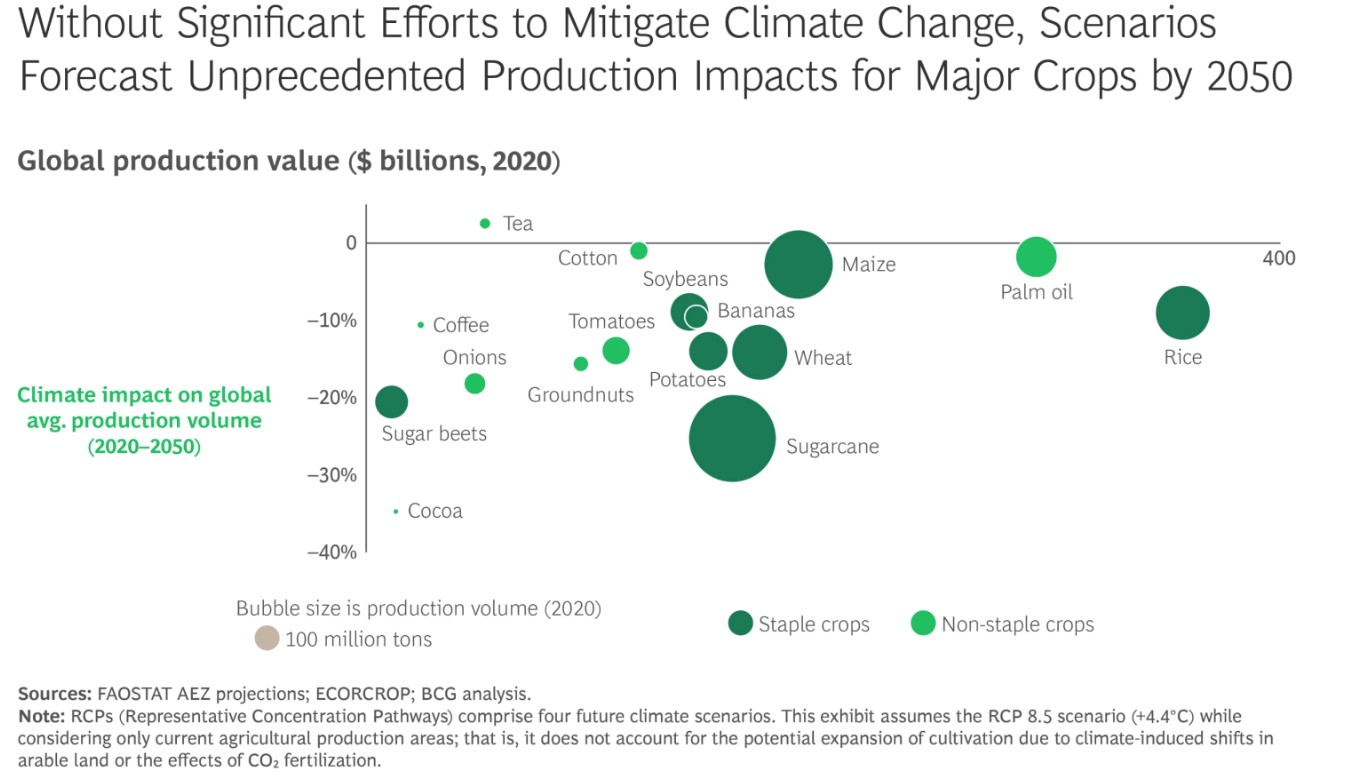

Agrifood supply chain resilience is a rising business risk; the number of days with moderate or high food price volatility for rice and wheat has doubled or tripled between 2020 and 2024. Climate risks could cut global crop production by up to 35% by 2050, with staples critical for Africa’s food security like rice, maize, and wheat particularly vulnerable.

A new analysis by Boston Consulting Group (BCG) and Quantis, Building Resilience in Agrifood Supply Chains, explores how rising climate risks, shifting trade dynamics, and evolving geopolitical conditions are colliding to make food supply disruptions more frequent, severe, and complex.

Food systems are already struggling: one-third of all food produced globally is lost or wasted, while the World Health Organization estimates that one in eleven people globally face food insecurity. Disruptions in agricultural production intensify this situation, rippling across communities, economies, and trade activity and reducing access to essential food supplies.

As geopolitical instability intensifies, supplies of staple crops such as wheat can be disrupted; the war in Ukraine is a case in point. Meanwhile, as climate change exacerbates both rising temperatures and the frequency of extreme weather events, unpredictable growing seasons may cause further disruption in existing agrifood production regions.

Africa stands at a critical crossroads

For Africa—where agriculture supports over half of the population’s livelihoods—this is not just a global issue, but an urgent local one.

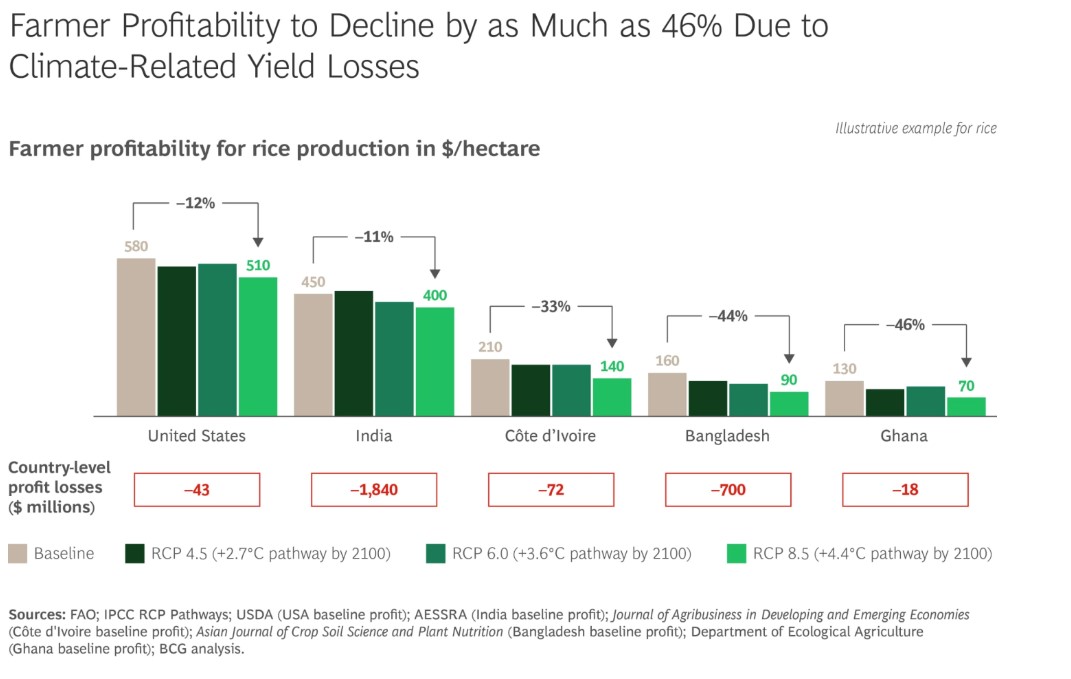

BCG’s analysis indicates that due to climate-related yield losses, farmer profitability could drop by as much as 46%. This threatens the financial stability of African smallholders, who make up about 70% of the agricultural production on the continent and are often without access to credit, insurance, or modern farming inputs.

Rice, a staple in many African countries, is expected to see global production declines of 9% by 2050, with top producers like India seeing up to 18% reduction. Export bans—like those India implemented in 2022 and 2023—could reduce global rice exports by 54% by 2050, posing a serious risk to African food imports.

“Rice production accounts for 22% of global caloric intake and production declines jeopardize food security for several importing nations in Africa,” says Hamid Maher, Managing Director and Senior Partner at BCG, Casablanca. “Action from public and private sector stakeholders is critical to speed up farmer adaptation and promote investment in innovation.”

The West African cocoa crisis

In West Africa, climate disruptions like erratic rainfall and diseases like swollen shoot and brown rot have severely impacted cocoa yields, pushing prices to nearly $13,000 per ton in December 2024—a staggering 400% increase over the 10-year average.

Although higher cocoa prices can potentially benefit African farmers as they may receive more money for their crop, possibly increasing their overall income, the benefits of higher prices don’t always fully reach farmers due to complex supply chains and intermediaries. Additionally, cocoa prices can be volatile, making it difficult for farmers to plan long-term.

One of the main challenges faced by producers is that global markets are increasingly exploring alternatives to Africa’s cocoa supply due to various factors. Markets are looking to Southeast Asian countries like Indonesia and Vietnam to increase cocoa production, while Latin American nations such as Ecuador and Brazil are also being considered for expanding cocoa cultivation with Brazil indicating ambitious plans to double domestic cocoa production by 2030.

The continent, which supplies over 60% of the world’s cocoa, is at risk of both economic and food security shocks, impacting millions of African farmers.

Pathways to resilience

As global supply chain volatility increases, companies can no longer afford to take a reactive approach to managing risks and addressing disruptions only as they emerge. For agrifood decision makers, building capabilities that can strengthen supply chain resilience is a priority.

“We believe this is a pivotal moment for agrifood decision makers to reimagine their approaches to create resilience, value and sustainability for their businesses and communities,” says Zoë Karl-Waithaka, Managing Director and Partner at BCG, Nairobi.

The report emphasises several key resilience levers for African agrifood systems:

- Investment in resilient seed varieties:Heavy reliance on a single crop variant exposes agriculture to pests, diseases, and climate challenges. For example, the Cavendish banana, which is the dominant variety cultivated and commercially grown in several African countries, including South Africa, Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Cameroon, and Ghana and accounts for 95% of commercial bananas sold globally, is extremely vulnerable to disease because of its lack of genetic diversity. To offset this, ensure more diversity by commercialising variants that have been developed by research institutions and as needed, promote and fund further research and development on existing variants to help them adapt to diseases and climate challenges, enhancing resilience and economic security for farmers.

- Use of predictive technologies such as AI and satellite imaging:The combination of in-soil sensors, satellite imaging, AI, and machine learning enables farm-to-fork traceability and on-farm monitoring. These technologies also support predictive analytics and advisory such as early warning systems which can be critical for planning and risk mitigation given changing weather patterns as well as precision agriculture, which cuts costs through a more targeted application of inputs such as soil nutrients and other agrichemicals.

- Crop and supply chain diversification:Crop sourcing often relies on dominant regions, making diversification difficult. Expanding sourcing and adjusting strategies through new suppliers and alternative crops requires significant investments and time for maturity. One solution is to identify alternative or underrepresented crops such as sorghum and millet. Others include expanding supplier bases, identifying crops that can adapt to the climatic and soil conditions of alternative growing regions, and harnessing global trade networks to ensure supply continuity.

- Access to climate finance for smallholder farmers:Unlocking transition financing and other forms of capital is essential to enable farmers and suppliers to adopt new technologies and farming practices and risk-mitigation strategies.

By investing in climate-smart agriculture, resilient seed varieties, and predictive technologies, Africa can build agrifood systems that are not only more secure, but also globally competitive and future-ready.