Within 40 days since the COVID-19 lockdown, a once unproductive plot of sand in the United Arab Emirates had become littered with ripe, sweet watermelons swelling under the Arabian sun.

Except it wasn’t so simple–these melons were only possible with the help of liquid “nanoclay”, a soil recovery technology whose story began 1,500 miles (2,400km) west and two decades ago.

These melons were only possible with the help of liquid “nanoclay”, a soil recovery technology whose story began 1,500 miles (2,400km) west and two decades ago.

Late in the summer, The Nile would expand onto the Egyptian delta plains because of the annual floods. The floodwaters carried minerals, nutrients and clay particles from the East African drainage basin that feeds the Nile depositing them across the delta lands resulting in the drop in land fertility

Ole Sivertsen, chief executive of Desert Control, explains that the presence of clay in the right proportions greatly changes the inability of thin soils to retain moisture.

According to University of Edinburgh soil scientist, Saran Sohi, using clay to improve soils comes at the cost of labour intensity and disruption to underground ecosystems. Ploughing, excavating and turning the soil also comes at an environmental cost as it exposes sequestered carbon to oxygen and it loses into the atmosphere as carbon dioxide. Coupled with this is the disruption to the complex soil biome that comes with cultivation.

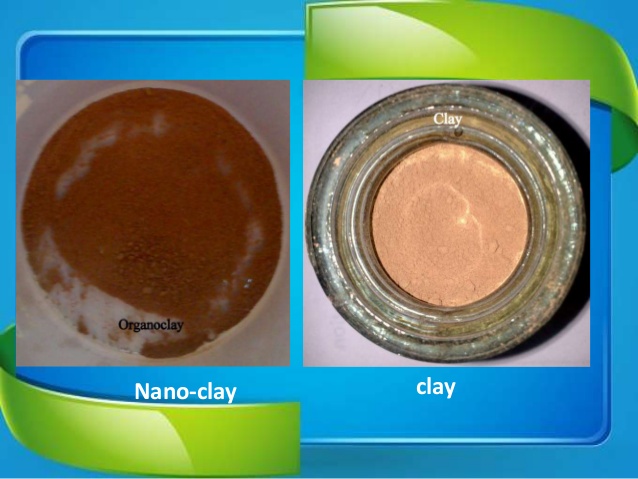

The result of the research to find a thin, balanced, liquid formula that easily percolates through tiny particles of local soil but does not drain so fast that it freely seeps out and is lost result is a 200-300 nanometer layer of clay around each sand particle that creates a snowflake-like formation. This increased surface area allows water and nutrients to stick to the sand and chemically combine with it rather than being lost as runoff through the soil.

“The clay mimics organic matter in its functionality, helping soils retain water, and allowing the soil flora and fauna to gain a foothold,” says Sivertsen. “Once you have clay particles stabilizing conditions and helping make nutrients bioavailable, you can plant crops within seven hours.”

While the technology has been in development for almost 15 years, it has only been set on the path to commercial scaling in the past 12 months after being independently tested by the International Center for Biosaline Agriculture (ICBA) in Dubai.

“Lockdown in the UAE was very strict and their imports plummeted, meaning fresh produce was unavailable to many,” says Sivertsen. “We worked with ICBA and the Red Crescent team to get the fresh watermelons and zucchini to individuals and families nearby. The aim was to test it all for the higher nutrition levels we suspect crops grown under such conditions may provide, but that will have to wait for the next trial plot.”