A resent research by a team of scientists has indicated how selective deforestation by tobacco farmers in Uganda is threatening the spread of bat-borne viruses among wildlife and humans.

The research titled ‘Selective deforestation and exposure of African wildlife to bat-borne viruses’ published this week by Communications Biology, shows that the international demand for tobacco lead local farmers to start cutting down a specific palm tree, Raphia farinifera, a rich source of dietary minerals for wildlife.

This tree’s tough, peelable fronds has been helping the growers to make strings on which to hang tobacco leaves to dry and as a result, R. farinifera nearly disappeared from Uganda’s Budongo Forest between 2006 and 2012.

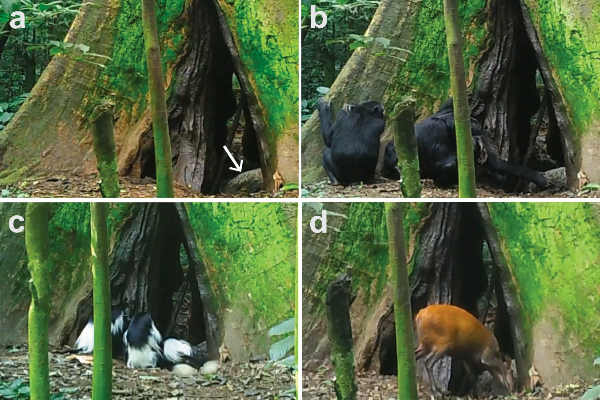

This lead to selective deforestation and since then there has been loss of a primary source of dietary minerals for chimpanzees, black-and-white colobus, and red duiker causing a fallback consumption of bat guano by the wildlife exposing the animals to bat-associated viruses, including a congeneric of the pandemic SARS coronaviruses.

Budongo Forest Reserve, western Uganda, contains approximately 482 km2 of medium-altitude, semi-deciduous forest and is located in the Albertine Rift, a region of exceptional biodiversity and endemism.

Until approximately 2008, the swamp forests of Budongo contained Raphia farinifera, a palm that, when decaying, provided a high-quality source of essential dietary minerals to wildlife

The wildlife alternative diet

Field staff and scientists at Budongo have noted that the chimps and other wildlife consume a variety of unusual substances, including bat guano, clay, and termite mounds. Researchers have discovered that animals in Budongo, much like those in other tropical ecosystems, encounter a shortage of dietary minerals, leading them to seek out these alternative food sources.

Bat guano proved to be an excellent alternative for chimpanzees and other animals. Although researchers are unsure how these animals learned to seek out guano, tests confirmed that the material is rich in sodium, potassium, magnesium, and phosphorus.

According to Tony Goldberg, a wildlife epidemiologist at the University of Wisconsin–Madison and one of the lead scientists in this study, bats are good creatures but they do carry dozens of viruses.

“Our metagenomic analyses of bat guano identified 27 eukaryotic viruses, including a novel betacoronavirus.”

The research results suggest that guano consumption by Budongo wildlife may be a behavioral adaptation to mineral scarcity. This inference is supported by a decades-long body of evidence showing that wildlife in Budongo have responded to the disappearance of R. farinifera by seeking alternative mineral sources

Further findings illustrate how “upstream” drivers such as socioeconomics and resource extraction can initiate elaborate chains of causation, ultimately increasing virus spillover risk.

Viruses’ spillover from wildlife to humans

Spillover of viruses from wildlife to humans is often thought to be preceded by viral transmission and amplification among wildlife. For example, human ebolavirus outbreaks in Africa follow sylvatic transmission cycles in non-human primates and ungulates, with humans likely becoming infected through contact with carcasses.

Similarly, epidemiological data and analyses of inferred viral genomic recombination suggest that approximately half of human-infecting coronaviruses underwent transmission from wildlife reservoirs to humans through intermediary hosts.

However, despite the high social and economic costs of zoonoses, the mechanisms underlying such antecedent virus transmission within animals remain poorly understood.

In fact, zoonotic diseases, or illnesses transmitted from animals to humans, account for about three quarters of new infectious diseases around the world, including some that could lead to pandemics.

The risk of a pathogen jumping from an animal to a human increases when people encroach on ecosystems and cause relationships to be disrupted between species—but how that risk actually becomes a reality can be unpredictable and difficult to untangle.