WHAT’S WRONG WITH THOSE FARMERS?

This story could only happen many years ago in a faraway land.

I bring it here for you as it was.

Once upon a time, in a faraway land, farmers worked their land from morning to night.

The land was plenty and fertile, the sun shone as it should, and sweat water was abundant within a short distance from their fields.

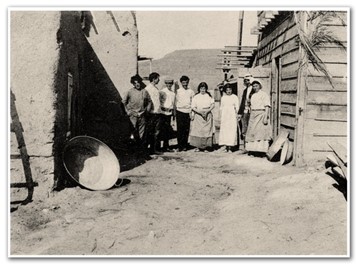

Although the farmers worked hard for long hours and gave all their strength, they barely managed to exist. They lived in austerity and poverty, suffering from diseases such as malaria, poverty, and hunger.

Fortunately for these farmers, in a distant land lived rich people, some of whom even bank owners, who saw the suffering of the farmers and their conscience yearned to help them.

The rich people sent the impoverished farmers significant financial support.

The rich people asked for nothing in return and benefited nothing from it; they did so for years out of goodwill, as a pure philanthropic act.

But the farmers remained poor, hungry, and sick as they were before.

So, the philanthropists thought that the farmers didn’t reach prosperity because they lacked proper advanced technological tools and plants to process the agricultural produce.

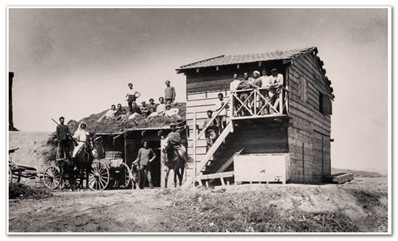

And so, the philanthropists gave the farmers, free of charge, many advanced technological tools and built buildings and factories to process the poor farmer’s agricultural produce.

But the farmers remained poor, hungry, and sick as they were before.

The philanthropists thought there was a problem with the knowledge of how to use the technologies and cultivate the land, and sent the farmers experts and advisers.

But the farmers remained poor, hungry, and sick as they were before.

The philanthropists didn’t give up; they said, “Maybe training in the villages is not good enough”, and built Training Centers, Centers of Excellence for the farmers.

But the farmers remained poor, hungry, and sick as they were before.

The philanthropists didn’t give up this time, too. They point out that the problem may stem from poor management capabilities.

So, they appointed professional managers to manage the Training Farm / Center of Excellence and the affiliated farmers.

But the farmers remained poor, hungry, and sick as they were.

Before we continue, please take a moment to answer those simple, straightforward questions; it is essential before the next part.

* Could such a chain of events happen in your country?

* Why those actions didn’t bring the expected results and changes?

* What should be done differently?

* If this was a play, how do you think it ended, and how would you like to see it ending?

* Without looking at the pictures, where do you think those events took place?

THE TURNING POINT

The events described above are not imaginary; they took place in reality between the middle of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century.

But this was not the end of the story, only some chapters in a never-ending story, which developed in ways that no one had predicted, for it had never happened before.

When things looked like they couldn’t get any worse, they worsened.

Despite the Training Farm’s ample resources — including land, water, sunlight, dedicated workers, state-of-the-art technologies on-site, financial backing, and oversight from an expert agronomist — it perplexed everyone that, rather than achieving an 11% profit by year-end (as promised by the manager), the farm incurred significant losses.

What did the manager do?

The farm manager began to scold the workers and was not always careful with his language.

On the other hand, the workers accused him of mismanagement and miserliness.

The fuel fumes were in the air, and a spark was required to ignite that emotional time bomb.

The spark appeared when the manager invited non-community workers to speed up the work. The farm workers saw this as a violation of their dignity; some of the workers left the farm, and the rest, out of a loss of confidence, began a strike demanding the dismissal of the farm manager.

Then, something unexpected happened that would forever change the agricultural sector in that country and its history, as it created a new form of rural community.

To settle the conflict between the farm manager and the workers, the general manager, the one in charge of the farm’s manager (usually, he wasn’t on the farm), decided that the farm manager would not be fired and would stay for another year.

However, to mitigate resistance, the general manager, upon the workers’ request, allocated the farm’s land on the other side of the river to an independent group of workers (The Eight Group, seven men and one woman) for a one-year experimental period.

The general manager promised these workers that they would operate autonomously, without direct oversight from managers or supervisors, assuming full responsibility for their work.

They also agreed that if there were a profit, they would split it 50:50 with the Training Farm.

The general manager wrote about his decision to give part of the farmland to the workers to self-manage:

“Although I did not see clearly that we would do something here that would be of great importance regarding the development of rural communities in ____, my heart told me that this modest beginning might yield important results…”

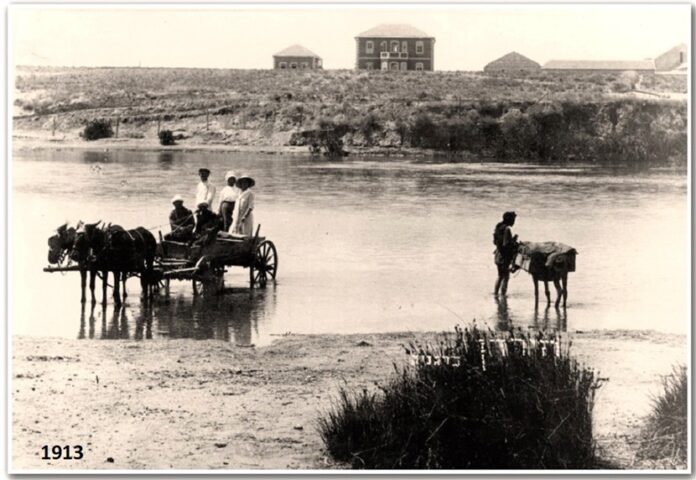

Freed from managers and with a burning desire to prove they could do a better job without the managers and supervisors (which they hated), the group crossed the river and immediately went to work. The title picture is from 1913, three years after that event.

Time passed fast, and as the year ended, they realized the economic results were beyond expectations.

Already in the first year, the group generated a decent profit, which, as agreed, was equally split with the farmland owners.

But wait, this is not the end because all the group wanted to achieve was to prove that they could farm without managers/supervisors. So, after they split the profits, they left the new farm they had just founded.

But the new farm didn’t remain empty; a new group came, one that agreed to take permanent responsibility for the place.

The new group called themselves Group Dgania, and their primary motivation was to establish a farmers’ group that was driven to work out for freedom and independence from outside managers and supervisors based on cooperation and equality.

Despite all the limitations of the first years, Group Dgania managed to sustain itself without deficits and, in the process, proved the economic advantages of the new type of rural organization structure over any other existing ones.

Everybody heard about the success of Group Dgania, and many came to visit, to become part of it (for good or for a while), and mainly learn and copy its success secrets.

As a result, in only a few decades, hundreds of other Group Dgania lifestyle groups emerged, all thriving and prosperous.

This blossom of thriving agro Groups created a vibrant, prosperous agro sector with a sound economic basis, which later enabled the formation of a new-old nation with an outstanding, advanced, and innovative economy.

Have you already guessed which country and event this story describes?

BEHIND THE SCENE

The story above, though it could have taken place in any of the current developing countries, in reality took place in Israel.

Yes, the same Israel that some believe had always had a prosperous agro sector began far from prosperity and success, with a long chain of program failures and human despair.

At that time, Israel was still colonized by the Ottoman (Turkish) empire from the late 19th century to the early 20th century.

From the mid 19 century, significant efforts, backed by wealthy European philanthropists, took place to bring prosperity to the land of Israel through inhabiting rural communities that would work the land.

The environment was harsh and hostile; many died from malaria and other diseases and were killed by the attack of outlaws.

The story frames the transition period from a village-like community called in Hebrew, Moshava, where each family is a stand-alone economic unit, to a togetherness-based community founded on cooperation, equality, and sharing principles, known to us today as Kibbutz and Moshav.

Kinneret – The Training Farm I refer to in the above story, which today we would name A Center of Excellence, is called Kinneret, situated next to the Sea of Galilee and where the Jordan River leaves it on its way to the Dead Sea.

Dr. Arthur Rupin – It was Dr. Rupin who, as part of the compromise following the conflict between the manager and the workers on the Kinneret Training Farm, suggested that a group of workers (The Eight) get part of the Kinneret farm on the other side of the Jordan River to work and manage by themselves, as they understand.

When the first group decided to leave the new farm after a year, Dr. Rupin offered another group to settle in the same place, but this time permanently and owning the land.

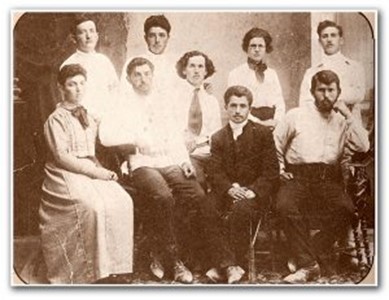

Group Dgania / Kibbutz Dgania, the successor to The Eight Group, leveraged their predecessor’s business acumen and practical insights in farm management, integrating their own values of cooperation, equality (including gender equality), and self-management.

Group Dgania (Dgania, from the word Cereals in Hebrew) was founded on October 28, 1910, and hence became the first Kibbutz. It laid the foundations for the birth of hundreds of other Kibbutzs, which played a significant role in paving the road to the State of Israel.

P.S. At the same time (1911) and not far away, another type of rural community based on cooperation made its first steps, the Moshav. It took three more years before the village Merhavia was transformed into Moshav Merhavia, which opened an additional path to a thriving type of rural community, also based on cooperation!

Kibbutz – Kibbutz is the translation of the word Group in Hebrew. Kibbutz/Group represents the superiority and power of the togetherness, the group, over the individual.

Size of the Groups – the groups in this story, which impact and founded communities, typically range from 3 to 12 people, and often there is one that is more active than the others.

A big vision is not limited or measured by the number of people or the means they have when initiating it.

Goals and Values – The goals and values that led to the establishment of The Eight Group and later to the establishment of Kibbutz (Group) Dgania and other groups that followed its path and established thriving rural communities in its image were formulated over several years by young, motivated people. Above all, the motivation of young people fueled the endless attempts to reach economically sustainable, thriving rural communities.

Failures and Persistence – The Kibbutz was not the first choice of those wishing to see a prosperous, thriving agro sector in the emerging new Israel; it was the outcome of endless failures and the first thing that worked properly.

Thomas A. Edison lived and acted in the same period as our Kibbutz creation story. It is said that Edison made 1,000 attempts at the long-lasting lightbulb before it worked. When asked how it felt to fail 1,000 times, he said, “I didn’t fail 1,000 times. The light bulb was an invention with 1,000 steps.”

The young Israeli pioneers didn’t fail 1,000 times; the Kibbutz was an “invention” where 100’s of people took part and with 1,000’s of steps.

Thanks to Edison’s innovation, we enjoy light everywhere and anytime we like.

I believe that one day, thanks to the social innovation that the Israeli pioneers brought to the world in the form of the Kibbutz and Moshav, we will see plenty of thriving rural communities worldwide as we see them in Israel.

We live in a society that sanctifies and glorifies success but is unforgiving to those who fail and unaccepting the fact that the road to progress and success is always paved with failures.

Remember that failures and persistence are part of the building blocks of success.

Technology – was as basic as one can imagine in the early 20th century: horses and primarily manual labor. There were no tractors, computers, or drones. Only several years after Kibbutz Dgania was founded and was already economically established, the first water pump arrived to help irrigate the fields.

The most significant story in modern times of transitioning from impoverished to prosperous rural communities occurred over a century ago. Have you noticed that technology is not mentioned as a critical success factor in that transition?

Success – When agro-community success arrived, it was easy to see, and everybody instantly recognized it. The success came from changing the rural organization’s socio-business model. The new model was based on principles that are easy to replicate or copy and adapt, hence the success of the communities that followed it and copied its model.

National principles – Already in 1903, the Jewish leadership, i.e., Zionists, established guidelines for the return of the Jews to their Promised Land:

(A) The Zionist settlement should be based primarily on agriculture and not on urban.

(B) The settlement should not be based on support and donations but rather on credit that will be given to the settlers without capital at low interest and in payments for an extended period.

(C) The land will forever remain the nation’s property, including the land on which rural communities will be established. It will stay in the hands of its employees on lease as long as they work it.

What would you take from the above to solve rural communities in modern times?

THE EASY STUFF IS THE HARDEST

In many developing countries, most of the population are farmers living in poverty in rural communities. This is why 550 million smallholders live in poverty.

What would you wish them?

I wish them to live a life of dignity by producing abundant healthy food in a healthy environment.

The new-age Israelis, the Zionists, realized over 100 years ago the linkage between farmers’ prosperity and that of the emerging nation and hence invested endless efforts in pulling farmers out of their misery and poverty.

Like in any sector and factory, the workers always know better what is wrong and how to fix it. Eventually, the Israeli workers, not the experts and managers, came up with the idea of the Kibbutz and practiced it as they understood it.

They were lucky to have a supportive environment and visionary people that enabled them to execute their dreams.

Oh, and success came not without pains and endless failures over decades.

This story I share with you has one purpose and one goal: to deliver a message.

THE MESSAGE

Look at Israel, a country considered “an economic miracle” and a leader in global agriculture; its starting point is no better than most modern developing countries.

Look at the transition of the Israeli farmers and agro sector from sickness, poverty, and hunger to today’s prosperity.

Were Israel’s farmers’ difficulties any easier or different than those farmers in developing countries encounter today?

Did Israeli farmers in the late 19th century and early 20th century have something farmers in developing countries don’t have today?

If your answers to the above questions are NO, what stops you from changing your rural communities and country?

Most people view finance and technology as limited factors for farmers’ prosperity. Without saying finances and technology are unimportant, do you still think they are the leading factors preventing farmers from reaching sustainable prosperity?

In contrast to expectations and after decades of hardship and struggle, the Israelis realize the critical success factor is the organization model of the rural community, which includes its business model, values, goals, etc.

Not the finance nor the technologies, which we view as “hard to achieve”, gave the Israelis their agricultural edge. No, it was the soft skills, such as community organization, management, human relations, and above all, values, which we view as “easy to achieve”.

When Edison invented the lightbulb, he created a model that was easy for others to see, understand, and copy.

Indeed, within a few years, the principles of light bulbs were copied and manufactured worldwide, which created many jobs and benefited millions of users.

Developing the first product, service, and model is far more challenging than copying them once realized.

Now that we have the Kibbutz and Moshav rural communities successful models, all we have left is to adapt and implement those principles and values, with the required local adjustments, to bring sustainable prosperity and happiness to all rural communities.

Can we do this, or is this too much?

Dr. Nimrod Israely is the CEO and Founder of Dream Valley and Biofeed companies and the Chairman and Co-founder of the IBMA conference.