- African nations must build their own research capacity, rather than relying solely on Western institutions and donors.

- Africa remains largely overlooked in HIV sequencing research, despite bearing the greatest burden.

- It is time for Africa to reclaim agency over its health future.

- Global HIV research is biased towards the West: 54% of studies focus on just 12% of the virus.

- Ignoring HIV diversity could trigger the next pandemic, scientists warn.

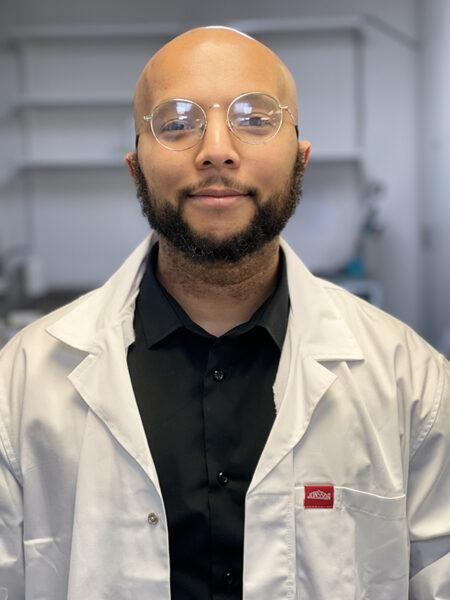

The global fight against HIV-1 has often been framed as a success story of science, funding and international collaboration. But as the virus evolves, so too must our strategy. A recent commentary in Nature Reviews Microbiology, led by Dr Monray Williams of the North-West University (NWU) in South Africa, issues a stark warning: global complacency must end, and sub-Saharan Africa must be placed at the centre of the research agenda, or risk losing control of the HIV-1 epidemic.

Despite accounting for more than two-thirds of global HIV-1 infections, sub-Saharan Africa remains a research blind spot. Most studies continue to focus on subtype B, common in the West but representing only 12% of global cases. Subtype C, which is responsible for over half of global infections and dominant in sub-Saharan Africa is significantly understudied. This imbalance, argues Dr Williams and his co-authors, undermines the development of effective treatments, vaccines, and, ultimately, a cure.

The message is sobering. HIV-1’s remarkable diversity, driven by its error-prone replication and frequent recombination, makes understanding its many forms crucial. Subtype-specific variations influence everything from disease progression and drug resistance to vaccine effectiveness. Yet, 54% of global sequence data derives from subtype B, compared with a mere 15% from subtype C. Even key viral proteins, such as gp120 and Nef, are far better characterised in subtype B.

Dr Williams, a researcher in the Biomedical and Molecular Metabolism Research Unit at NWU, puts it plainly: “We cannot end a global pandemic by studying just a fraction of its biology.” The data he and his colleagues present are stark. The Congo Basin – thought to be the origin of the HIV-1 pandemic – holds the highest viral diversity, yet remains largely unexplored. These unstudied lineages may contain forms resistant to current interventions or capable of fuelling future outbreaks.

South Africa, among the countries hardest hit by HIV, ranks third globally in research output. Yet even here, subtype B dominates scientific focus. Subtypes A, D, and numerous recombinant forms, each with distinct clinical and epidemiological profiles, are dangerously under-analysed. The commentary warns that this neglect could prove disastrous if new variants arise with increased transmissibility or drug resistance.

However, the authors do not stop at diagnosis. They propose a bold corrective strategy aptly named HARNESS to address these disparities and reshape the global health research landscape.

At its core is the principle of self-reliance. African countries must strengthen their own research capabilities by investing in local laboratories, biobanks, genomic surveillance systems, and, critically, the training of future scientists. Alarmingly, Africa currently contributes just 2% of global biobank authorship, a shortfall that threatens sustained progress.

The paper also advocates for deeper South–South collaboration. By exchanging data, tools, and expertise within Africa and across the global South, the continent can pioneer a fairer, more representative research model. Funding, too, should reflect disease burden—not the preferences of external donors. Too often, foreign aid distorts priorities in favour of Northern concerns, leaving African researchers underfunded and marginalised.

Structural reform is essential to challenge the dominance of Northern institutions in setting the global health agenda. African-led research must be ethical, accountable, and community-driven—sensitive to the cultural and socio-economic realities that shape public health. As Dr Williams and his colleagues argue, reducing stigma, ensuring equitable access, and listening to affected communities are as vital as gene sequencing.

Recent cuts to global health initiatives such as PEPFAR have heightened the need for regional autonomy. Yet Dr Williams sees opportunity amid retreat. “This is the moment for Africa to reclaim agency over its health future,” he writes.

This is not merely a scholarly contribution, it is a rallying cry. The end of the HIV-1 pandemic will not be dictated from Brussels or Boston alone. It will emerge from the laboratories, clinics, and communities of Africa if the world is wise enough to invest accordingly. The science is conclusive. The politics, as ever, remains the harder struggle.